I’ve often wondered why human beings are so focused on intent. In South Africa, evidence of a crime requires proof that the perpetrator intended to act unlawfully. Underlying the legal requirement of intent is the assumption that intentions become visible when someone does something with them (to paraphrase Frank Sonnenberg). I would argue that it is near-impossible to determine, with a fair amount of objectivity and certainty, if someone’s intentions were honourable or wicked, irrespective of whether their behaviour was good or bad.

Can we connect intent with behaviour, beyond a reasonable doubt? Even when behaviour is virtuous, judging intent is mostly guesswork. And if someone treats you badly, does it really matter what their intentions are? We rinse-and-repeat harmful patterns, especially in our relationships, despite compiling long, experience-based lists of red flag behaviours. Not only are we bad at spotting other people’s intentions, but we are often unaware of our own intentions, unable to identify them correctly, or unable to deliberately turn our intentions into action.

Connecting behaviour to the impact it has on others further complicates things. Our experience of current events can blend effortlessly with the effects of previous experience. Suddenly being triggered by an event, person or experience comes to mind. This is why asking how and why someone’s actions affect us in a particular way is important. However, perpetrators of violence often use gaslighting and victim-blaming to excuse their abusive behaviour or argue away its impact. Let me be clear: the impact of violence cannot exist without the presence of violence, but the reverse (violence doesn’t exist in the absence of it having an impact) is simply not true. We might have empathy with offenders who have often been victims of violence themselves, but not by condoning their bad behaviour, and not at the cost of blaming ourselves for how violent behaviour impacts us.

Early this morning I was watching the graceful pair of hadeda ibises who have taken up residence in my garden. A summer shower had softened the soil. I was mesmerised by the rhythmic plunging of their long, slender, curved bills deep into the muddy earth. What were the odds of them finding enough sustenance with such seemingly random acts, I wondered. As it turns out, those distinct pokes are deliberate: ibises have cells hidden inside their bills that detect vibrations to identify food.

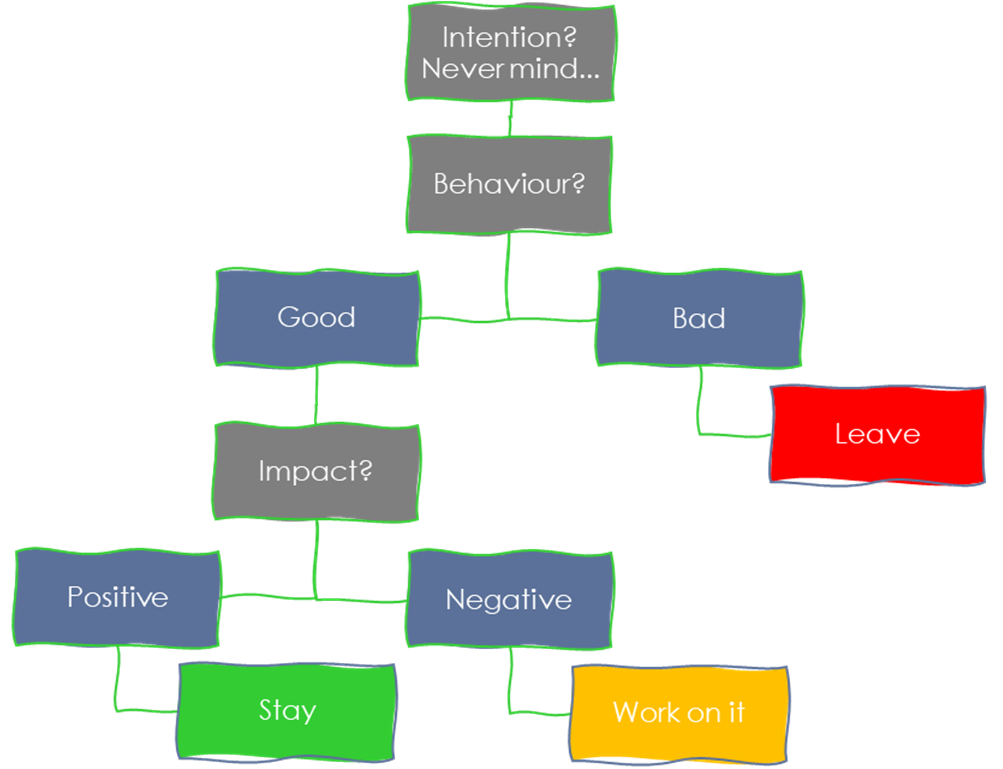

Here’s my hypothesis: the best way to deal with the muddy mess of life and relationships is to draw a clear distinction between people’s intentions (I), their behaviour (B), and the impact their behaviour has on others (I). Delve into each of these deliberately and separately, to detect what is good and what is bad. It is the separation of good intentions, bad behaviour, and painful impact, without contaminating any one of these with the others, which brings the clarity of mind and courage to walk away from harm.

It is never too early, or too late, to leave. When he doesn’t realise that he hurts you, when he doesn’t know why he hurts you, and when he knows why. Even if his intentions are good.

© Leonie Vorster 2023